Last updated: July 17th, 2023

Bicycle handlebars have an enormous impact on your riding experience. The right ones solve posture and handling problems; the wrong ones worsen them.

But why are there so many designs, what’s with all the terminology, and which bars should you actually consider?

This article might contain affiliate links. As a member of programs including Amazon Associates, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Why are there so many types of handlebars for bikes?

Every bicycle handlebar design is a unique balance of efficiency, comfort, and control. Individual cyclists prioritize those factors differently, so dozens of handlebar styles have emerged to cater to them.

Some designs, like flat handlebars and classic North Road-style touring bars, try to balance all three factors. Others, like cruiser or aero (triathlon) bars, maximize one or two factors and disregard the rest.

Before we hop into the handlebar spectrum, let’s cover the terminology we use to describe it.

Bicycle handlebar jargon explained

Hand position

To start with the most obvious, hand position refers to the location and angle of your hands while riding.

All bike handlebars provide at least one basic position, but most have more. Generally, the more curves the bars have, the easier it is to find multiple hand positions.

Rise & drop

The vertical distance from the center of the stem to the center of the grip area.

- For drop bars, we call this—you guessed it—drop. In that case, the “center of the grip” would be the bottom of the hooks.

- For other styles, we generally call it rise, since the grip area is level with or above the stem.

Rise/drop, along with reach, directly changes riding posture and therefore speed and comfort. As mentioned above, more drop also increases the perceived reach, so it’s difficult to manipulate one without changing the other at least slightly.

Width

As you probably guessed, handlebar width is the distance from the left-most to the right-most portion of the bars.

Wider bars give better control and stability, since they maximize leverage against the steering axis and against how the bike tilts to either side. Narrow bars encourage more aerodynamic posture and may “deaden” the twitchiness of an overly steep head tube angle.

Mountain bikes are an interesting case study in width. Vintage ones generally had narrow bars and a steep head angle, so they excelled at picking narrow paths between branches, but got a bit shaky at high speed. As trails became generally faster and gnarlier over the years, modern MTBs shifted toward slacker geometry and wider handlebars.

Reach

Reach is the distance from the center of the grip area to the center of the stem. This is a big factor in how stretched-out the rider sits, so it’s a major influence on the bike’s overall comfort and aerodynamics.

Keep in mind that drop bars reach forward from the stem whereas most other styles reach backward (toward the saddle). Consequently, switching from drop bars with 5 cm of reach to swept-back bars with 5 cm of reach would effectively shorten the cockpit by 10 cm. (Pragmatically, the difference in reach is one of several reasons we don’t often make a swap like that.)

Total reach (from the saddle) feels shorter as the same bars get higher. If you plan to play with stem or bar height, then you may need to replace your bars to maintain the same effective reach.

Long reach in either direction makes handling feel slower. It moves your hands farther from the steering axis, which means more rotation to turn the same number of degrees.

Extremely long reach (as on most cruisers) is a problem for aggressive or off-road riding. It allows for a huge amount of torque at the stem clamp, so the bars may rotate down when you hit a bump.

Flare

On drop bars, flare is the angle at which the hooks tilt up and out from vertical. The main benefit is a wider hand position for better control over rough terrain.

The hooks are the widest point on any drop bar. They also provide the best brake leverage. Consequently, they’re the default hand position on rough terrain. So, when they flare out, the rider gets even more stability and control when they need it most.

As a secondary benefit, flared hooks are effectively shallower. That allows for slightly more upright posture, which can improve balance on steep, technical terrain. (It’s also more comfortable for riders with less-than-great back mobility.)

The wider, shallow grip isn’t too helpful on the road, so significant flare is more common on gravel, bikepacking, and “monstercross” bikes.

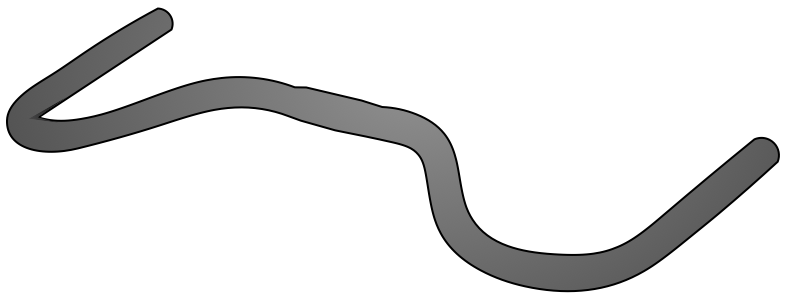

Back-sweep

Back-sweep is the horizontal angle at which the grip area bends backward from the stem. Perfectly straight bars have 0° of back-sweep since their grips and stem are in line. That’s not very ergonomic, so in reality, many “straight” bars (as on MTBs and hybrids) actually have a couple degrees of sweep.

On the other extreme, it may approach 70°–80° on some city and cruiser bars. Forward sweep, to my knowledge, is basically non-existent.

Up-sweep & down-sweep

Up- and down-sweep are the angles at which the grip area bends up/down from the stem.

At the risk of being pedantic, they’re not technically flat. Most flat bars and riser bars have 4°–5° of up-sweep. That’s generally thought to encourage a wide, stable elbow position for aggressive riding.

Swept-back bars often appear to have some down-sweep. Even if not, they’re usually rotated so the grips point slightly down and back. That sacrifices the strength and control of an elbows-out posture, but it’s easier on the wrists and works well for mellow, upright riding.

Diameter

Stem clamp diameter describes the center of the bars—where, as you’d expect, the stem clamps it in place. This is 31.8 mm on nearly all modern bicycles. You’ll also find 25.4 mm or 26.0 mm on older mountain and road bikes, respectively.

You can use a shim to fit a wider stem on narrower bars, but an exact fit will always give the best grip.

Grip diameter describes the portion where your hands typically rest while riding. This is conventionally 23.8 mm on drop bars (and some more obscure styles designed to accept road levers) versus 22.2 mm on nearly all others.

This is critical for brake lever and/or shifter compatibility. Generally, road levers only come in 23.8mm and others only in 22.2 mm, so you shouldn’t run into issues unless you’re attempting a drop-to-upright or upright-to-drop.

Now that we’ve covered the basic terms and trade-offs, here’s how bicycle handlebar types play out in real life.

I’ve split them into pavement-oriented and off-road-oriented styles, although there’s considerable overlap between the two. With each category, they’re sorted in very approximate order of popularity.

(Incidentally, there are many more styles that I haven’t mentioned. The variations below are popular at least in some tiny corner of the cycling world.)

Road & pavement bicycle handlebar types

Drop handlebars

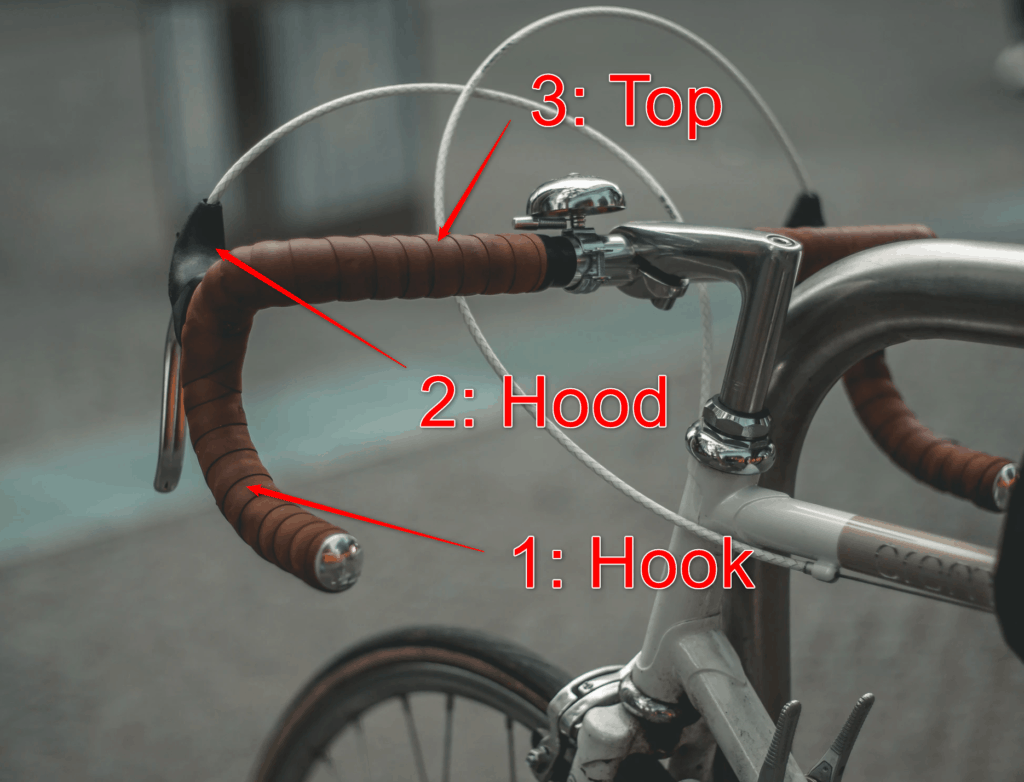

These are the quintessential road bike bars, with a down-and-back curve that provides three main hand positions:

- In the hooks, or the bottom of the curve.

- On the hoods, or the upper part of the levers.

- On the tops, or the narrow, flat section on either side of the stem.

There are also a couple positions in between these, but their usefulness depends on your bar shape, lever placement, and hand size.

Most road bikes use integrated brake-shifter levers, or “brifters,” which let you brake and shift without changing hand positions. Brifters are accessible from the hooks and hoods, but not from the tops. That’s why the tops are mostly used in situations where braking or shifting are unlikely: resting, cruising along, or sitting upright during a steep climb (to expand lung capacity).

Road bike bars lean toward the narrow side: typically 44 cm at most. Handlebar width is more generous for bikepacking and gravel purposes, but those bikes differ from road bikes in several other subtle ways, too.

Incidentally, that curvy shape makes it virtually impossible to fit grips. Instead, we wrap tape around them. Compared to grips, tape has the advantage of providing whatever thickness and contour the rider likes, and the disadvantage of being a general pain in the butt.

Aluminum is probably the most common material, but carbon handlebars are common on high-end road, gravel, and cyclocross bikes.

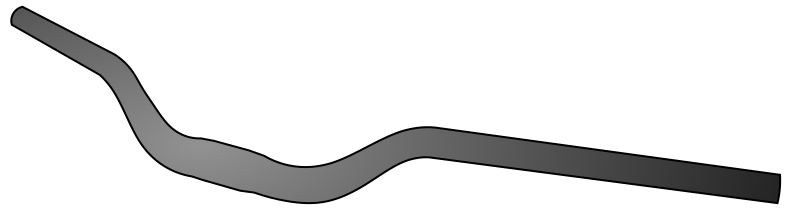

Upright/city/North Road handlebars

The classic North Road-style upright bars have been standard on transportation and leisure bicycles for probably more than a century. They go by several names, but “upright bars” might be the most universally understood.

The grip area approximates the natural resting rotation of your hands. That means moderate to significant back-sweep: akin to cruiser bars, but without the latter’s extreme rise and reach. There are multiple areas to grip, but the shifters and levers are conventionally toward the ends.

Many upright hybrids (plus classic English roadsters like the old Raleigh three-speeds) use a sportier version with modest back-sweep and short reach. The overall riding position is similar to that of flat or riser bars, but easier on the wrists.

On dedicated city bikes, including traditional Dutch models, sweep back to a nearly parallel hand position. You’ll also see this on modern variations like the albatross bars pictured below. Handling is less responsive, but the wrist angle is completely unstrained.

They’ve endured because of their delightfully ergonomic hand position. It comes at the cost of stability and control over rough terrain, but then again, they’re only spec’d on pavement-oriented bikes.

Cruiser handlebars

These handlebars have a simple, swept-back shape and are often made from steel. They provide a relaxed, upright riding position and are designed for casual riding styles. They’re visually similar to upright handlebars, but with an exaggerated shape.

So-called “ape hanger” bars are an extreme example, but basically relegated to novelty bikes.

As far as I know, they began in or around the 1930s as replicas of motorcycle cruiser bars. While stylish (to some) and fairly comfortable, their dramatic reach and/or rise are impractical for anything but a mellow ride with gentle curves. That shouldn’t come as a huge surprise given that cruisers began as more or less a children’s toy.

Bullhorn handlebars

These bars’ name comes from how their cut-off upward curves resemble a pair of horns. They’re effectively drop bars turned upside down, with the hooks sliced off.

Bullhorn bars originated in track racing. Track bikes don’t have brakes, so track racers needed a way to mimic the “hoods” position of drop bars without levers. It turns out that flipping and chopping drop bars accomplishes exactly that. That was refined into a very similar but more contoured form called pursuit bars.

Track bikes influenced bike messenger culture, which in turn brought fixed-gear bikes and their bullhorn bars to city streets.

Today, bullhorn bars are readily available off the shelf, and you’ll commonly see them as stock equipment on fixed-gear bikes. They remain a popular DIY project on fixed-gear conversions of vintage road bikes, too.

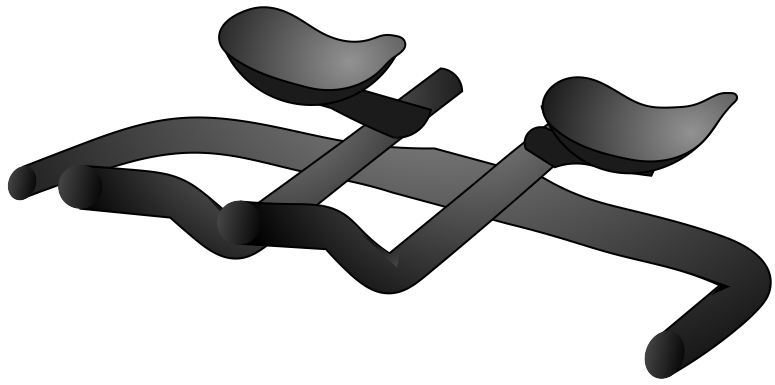

Aero handlebars

Aero bars (or “tri” bars) stretch the rider out into the most elongated, aerodynamic position possible. The elbow support bears weight while the upward-sloping end section provides a grip.

Aero bars are standard for triathlon and time trial racing, but also used by gravel, long-distance, and recreational riders who find the position fast and comfortable.

There are two standard ways to buy aero bars:

- Clip-on aero bars for existing drop or flat bars. These are strictly the arm extensions, not the main bar/grip area. These are ideal for occasional racers or non-racers who don’t need a separate, dedicated bike. Clip-on bars generally don’t have brake levers or shifters, since they’re just a supplement to the drop bars.

- Full aero handlebar sets that include both a main bar/grip area (in place of drop bars) and the arm extensions. These typically have brake levers and shifters (separately, not as integrated “brifters”) so the rider doesn’t need to leave that position during a race.

If aero bars are so efficient, then why doesn’t everyone use them? In short: handling. With narrow and outstretched arms, it’s tough to control the bicycle on anything besides smooth pavement with gentle curves.

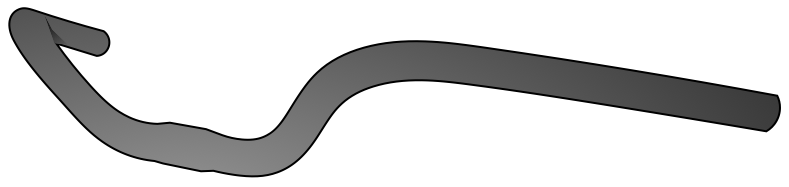

Mustache handlebars

Mustache bars are the result of flaring drop-bar hooks nearly all the way out (i.e., nearly 90°). They still take road levers, so they’re a reasonably popular choice for road-bike riders who want a modestly more upright position.

Most mustache bars are around 52 cm wide, or ~10 cm wider than drop bars. You can expect better off-road control, and more comfort when riding in the hooks, but a slightly less aerodynamic posture.

The hooks, hoods, and flats are still accessible as hand positions. The hoods and tops are now along the same plane, however, so they’re less ergonomically different than on drop bars.

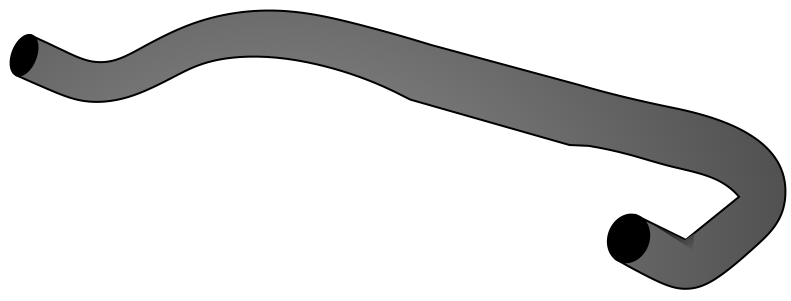

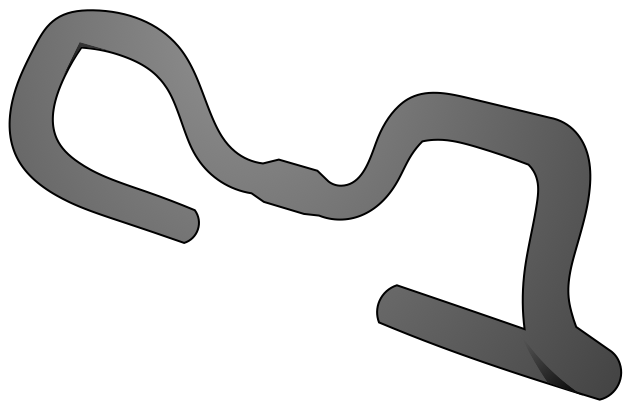

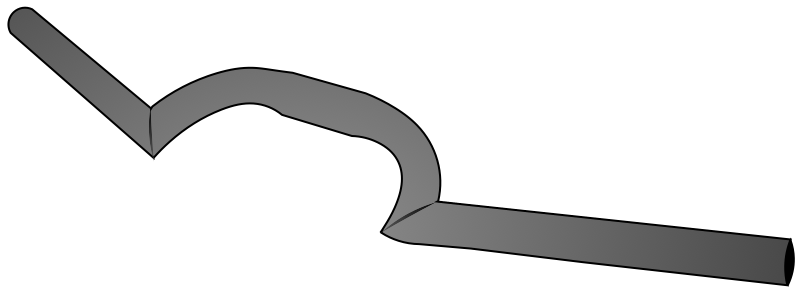

Butterfly/touring/trekking handlebars

Named for their wing-like appearance, butterfly bars offer at least three main hand positions with varying uprightness, aerodynamic, and leverage.

They’re fairly popular for road touring, since the sheer variety of hand positions makes it easier to stay comfortable. The outer and upper “wings” are functionally similar to very long, integrated bar ends.

Recumbent handlebars

Universal on recumbent bikes but unseen elsewhere, these U-shaped bars actually come in a few varieties.

Most resemble a rotated set of swept-back riser bars. Others are similar to flat bars and most often appear on recumbents with extended stems.

Porteur handlebars

Porteur (“transporter”) bike handlebar probably emerged on French newspaper delivery bikes circa 1940.

They’re characterized by a backward sweep approaching 90°, a far narrower width than on other swept-back styles, and sometimes a rise of multiple inches.

Porteurs of the day preferred road bikes due to their speed and agility, but needed front rack clearance for their sometimes enormous cargo, as well as a broader field of vision. The back-sweep and rise met those needs, while the narrowness helped them snake through the packed streets of mid-century Paris.

Today, I see them used mostly in retro porteur-inspired builds, as well as the occasional road bike-to-city bike conversion.

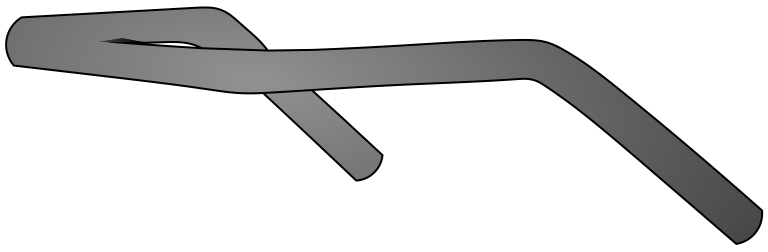

Condorino handlebars

As our first step into truly obscure styles, condorino bars are a motorcycle-esque design seen on vintage Italian road bikes.

The signature C-shaped center greatly increased the reach of an otherwise flat bar with slight back-sweep. This offset the relatively short top tubes that characterized older road bikes.

Condorino bars essentially vanished by the 1980s, although a few unorthodox brands like Soma have resurrected them from time to time.

Off-road, all-around & misc. bicycle handlebar types

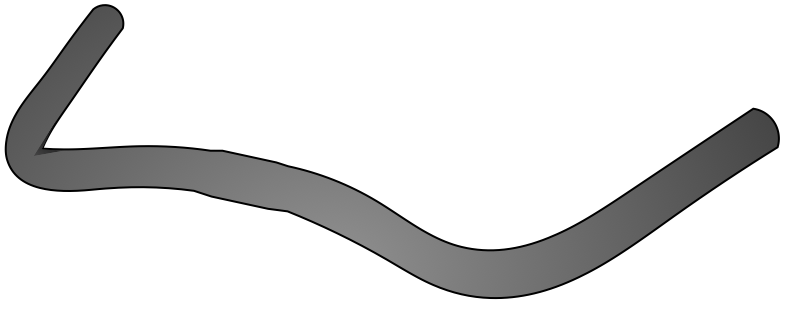

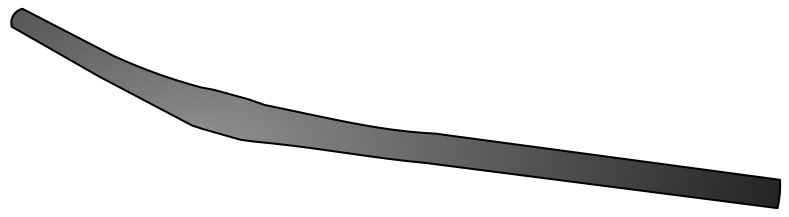

Flat (“straight”) handlebars & riser handlebars

Flat and low-rise handlebars are the standard hybrid and mountain bike handlebars. Strictly speaking, most aren’t totally flat, but actually have a couple degrees of up-sweep and back-sweep.

For all practical purposes, flat and riser bars perform identically. They differ only in posture. Risers are helpful on frames with very low stack height, so they’re quite common on “long and low” modern MTBs.

High-rise bars are available, but it’s typically limited to about an inch. Beyond that, a higher stem (or different bike) is preferable. Much higher rise may create too much torque for the stem clamp to prevent rotation.

As with drops, these are often carbon handlebars, but aluminum is the most prevalent.

BMX handlebars

BMX handlebars are nearly straight in the grips, and feel much like a flat bar when properly sized.

Their extremely high rise offsets the low stack height of a BMX bike. The distinctive cross-bar—often wrapped in a pad—prevents flex in the high-rising center section.

BMX bars are used for exactly what their name suggests, and nothing else—at least not conventionally. Their construction may be sturdier or lighter, depending on what kind of BMX bike (race, freestyle, or dirt-jump) they’re intended for. Carbon bars are popular among racers, but freestyle riders lean toward chromoly steel.

They do resemble the so-called “klunker” style of MTB riser bars, but as far as I can tell, they arose independently.

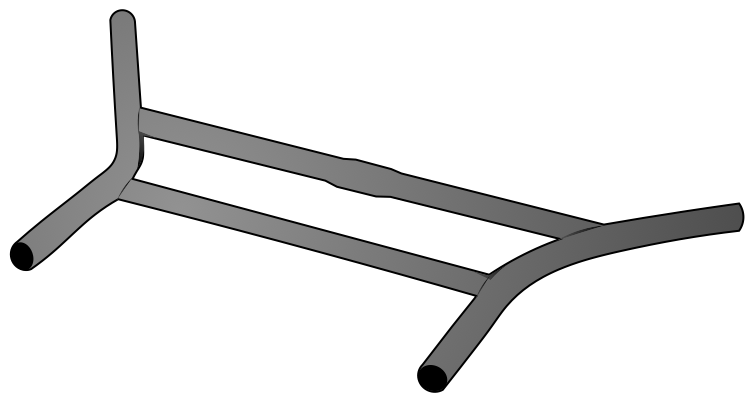

Alternative handlebars

“Alt bars” comprise…well, all other bike handlebar types. There are no clear criteria, since they’re a catch-all by definition. Some of the most common include:

- Jones H-Bar (and several imitations thereof)

- Bullmoose bars (like the swept-back flat bars seen on 1980s MTBs, with a non-adjustable integrated stem)

- Klunker bars (similar to BMX bars, but wider, more swept back, and lower in rise)

- Even harder-to-categorize designs like the Surly Moloko and Velo Orange Crazy Bars

Most are based on a conventional style, but with altered hand positions and/or accessory mounts. They often look quirky—as if a couple “normal” bar styles were fused together—but are eminently practical.

The Jones bar is probably the most successful, so much so that I hesitate to call it “alternative.” Velo Orange and Nitto are the go-to brands for alt bars, but you’ll find plenty of choices from Surly, Soma, and Fairweather, among less familiar names.

So, which handlebars are right for me?

Different riding styles benefit from different bike handlebars, but there’s quite a bit of room for individual preference.

It’s well worth experimenting. However, before you go making changes, remember that drastic differences in the cockpit will affect your posture, handling, and even bike seat comfort. It’s best to test subtler changes—like more sweep or higher rise or shorter reach—rather than everything at once.

One other caveat: locking bike handlebar grips are effortless to install and remove, but slip-on grips are a nightmare. If you’re planning to try multiple bar styles in succession, then it’s worth dropping some cash on lock-on grips while you’re at it.

For all-around use

For all-around transportation, recreation, and fitness, start with modestly swept-back upright bars such as the North Road style. They’re the most versatile and ergonomic, since different variations support a moderately forward or totally upright position while minimizing wrist strain.

They also make viable road bike handlebars if you’re one of the many for whom a standard drop bar isn’t comfortable. Just pay attention to reach before attempting an upright conversion!

If you prefer speed and power over comfort—and that’s perfectly reasonable, too—then a straight bar or lower, swept-back riser bar is a more efficient choice. The forward-leaning position isn’t as comfortable, but it’s highly efficient.

For long-distance road & gravel cycling

Drop bars have extremely high rise to offset the extremely low stack height of a BMX bike. due to improved aerodynamics and more variety of hand positions. They’re generally narrower handlebars, which should place your hands roughly in line with your shoulder width.

You may wish to experiment with clip-on aero handlebars, too. They give your stock drop bars yet another hand position that improves aerodynamics and gives your wrists a break.

Gravel bikes benefit from increased width, if only by a few centimeters. Narrow handlebars may undermine control on rough

For an aggressive MTB or urban riding style

For aggressive mountain biking or urban riding, choose flat bars, or low-rise bars. They provide the best leverage and control, so they’ve been the default on default mountain bikes since (almost) day one. They also encourage you to lean forward for greater power and more even weight distribution.

A straight bar will maximize control during aggressive MTB riding, whereas a riser bar with modest back-sweep suits for hybrids and city bikes.

Both flat and riser bars accept bar ends, so you can easily add multiple hand positions for comfort on longer rides. But think twice about bar ends for singletrack riding, since they’re liable to catch on brush.

Grips matter, too!

All types of handlebars feel and perform best with the right grips. In most cases, that means an ergonomic pair that alleviates pressure points and feels secure when wet.

Now that you know which handlebars to consider, check out my guide to bike handlebar grips to learn how to get the most out of them.